Shows That Give Off Pleasure, and a Bit of Body Heat

Among the fall’s surveys of contemporary art, I’m most excited about “Made in L.A. 2023: Acts of Living,” (Oct. 1 -Dec. 31) the sixth incarnation of the Hammer Museum’s always enlightening biennial survey of Los Angeles-area art. Its illustrated checklist — all there is to go on before a show actually opens — is palpable with hand making and color. It has body heat.

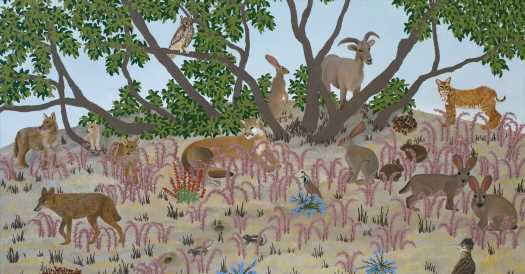

There’s an undercurrent of assemblage to many of the paintings and objects in the show, most evident in the frequent use of found objects and materials that add new strands of political thought. Some works reflect the long arm of conceptual art; more perpetuate outsider and folk art, craft and Indigenous traditions, as with the paintings of the self-taught octogenarian, Jessie Homer French.

Back in New York, two of the Los Angeles art scene’s heaviest hitters — born 20 years apart and emblematic of very different phases of the city’s cultural history — will take over substantial amounts of space in major museums. The Museum of Modern Art will fill its vast sixth floor with “Ed Ruscha / Now Then” (Sept. 10-Jan. 13, 2024). The most comprehensive survey to date of the artist’s six-decade career, it displays 200 works, starting in 1958, two years after Ruscha, a clean-cut high school graduate from Oklahoma, arrived in L.A., intending to study commercial art. A subversive notion of fine art interceded and Ruscha came to epitomize ’60s L.A. (mostly white) cool with works that often elevated the relatively modest forms of films, photography and artists books, as well as paintings that had the glossy lightness of ads.

The Whitney Museum will turn most of its vast fifth floor over to “Henry Taylor: B Side” (Oct. 4-Jan. 28, 2024). Can I just say: Finally!? During its six-month run at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, where it was curated by Bennett Simpson, Taylor’s retrospective vibrated with ecstatic reviews. Now it will be possible to see firsthand how Taylor, born in 1958, became one of this country’s greatest painters. His powerful, sometimes enigmatic images depict nearly every aspect of Black life in America, with occasional sendups of modern masterpieces. His achievement is essential to a moment when Black art is reshaping the whole of American art history.

Some of that reshaping should also be evident in “Unnamed Figures: Black Presence and Absence in the Early American North,” at the American Folk Art Museum (Nov. 15-March 24, 2024). This landmark effort will explore Black visual culture in New England and the Mid-Atlantic states from 1780 to 1850 in a presentation of around 125 portrait and landscape paintings, photographs, prints, needlework and stoneware jars, along with a 300-page catalog.

Two of the New York’s most cherished alternative spaces, both founded in 1972, are staging solo surveys of pioneering artists of different generations and distinctly dissimilar sensibilities.

MoMA PS1 will start its season with “Rirkrit Tiravanija: A Lot of People,” (Oct. 12-March 4, 2024) exploring in about 100 works the complex career of one of the progenitors of “relational aesthetics,” the movement that emphasized art as ephemeral and participatory over finite object. Tiravanija (born in 1961) threw down the gauntlet in the 1990s with SoHo gallery exhibitions in which he made and served pad Thai (1990, at Paula Allen) and Thai vegetable curry (1992, at 303 Gallery). Much followed in several different mediums, from T-shirts proclaiming “Fear Eats the Soul,” after Werner Fassbinder’s 1974 film, to chrome sculptures of furniture, with the best operating at the intersection of collective pleasure and political consciousness.

Artists Space will devote its large ground-floor galleries to “Jonathan Lyndon Chase: his beard is soft, my hands are empty” (Sept. 8-Dec. 2), exhibiting the painting, sculpture, drawings, videos, poetry and installations of this lavishly talented young Philadelphia-based artist. Chase exploded on the New York scene in 2018 with work that felt unprecedented in its exuberant yet tender portrayals of queer Black intimacy, including interiority, desire and daily life.

Regarding older art, nothing this season will match the scale and significance of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s “Look Again: European Paintings 1300-1800,” which opens Nov. 20. These galleries were expanded in 2013 and, consequently, rethought and rehung for the first time in 50 years.

It was the largest redo that the Met has ever undertaken. Not as much work as adding a new wing, of course. This couldn’t be better timed, given the social and political upheavals of the last decade and their effect on art, art history and museums. The news release promises increased diversity: “renewed attention to women artists,” “Europe’s complex relationships with New Spain” and “the histories of class, gender, race and religion.” Look again, indeed.

Elsewhere at the Met, the big names of art-history-as-usual will prevail. “Manet/Degas” (Sept. 24-Jan. 7, 2024) will examine the shifting friendship, rivalry and chilliness between these two great outliers of Impressionism. One of the chief draws of the show is Manet’s 1863 landmark “Olympia,” a painting of a nude woman whose comportment — straight spine and challenging gaze — has been seen as implicitly, if inadvertently, feminist. It caused a furor when first exhibited at the Salon of 1865. This will be its first visit to the United States.

“Vertigo of Color: Matisse, Derain and the Origins of Fauvism” (Oct. 13-Jan. 21, 2024), another pairing at the Met, will focus on the color revolution of Fauvism, formulated during the summer of 1905 by Henri Matisse and André Derain. Over nine weeks spent working together in Collioure, a coastal town in southern France, they laid a crucial chromatic cornerstone of modernism. Or maybe two: Their paint handling was often as raw as their palette.

Given the excessive attention to the rich and famous in all parts of American society, “Max Beerbohm: The Price of Celebrity” at the New York Public Library (Oct. 20-Jan. 28, 2024), feels right on schedule. The title seems a bit heavy and moralistic for “the incomparable Max,” as George Bernard Shaw dubbed him. But in London at the turn of the 20th-century, one price of celebrity was attention from this comic genius, whether in caricature, essay or his brilliant, sometimes illustrated letters. His subjects included Shaw, Oscar Wilde, Aubrey Beardsley and John Singer Sargent, as well as himself. In addition to 30 caricatures, this show includes photographs, letters, illustrated books and printed matter, and is the largest Beerbohm exhibition in this country in decades.

Roberta Smith, the co-chief art critic, regularly reviews museum exhibitions, art fairs and gallery shows in New York, North America and abroad. Her special areas of interest include ceramics textiles, folk and outsider art, design and video art. More about Roberta Smith

Source: Read Full Article