Small Talk, Big Looks: An Interview with NYC's Small Talk Studio

This article originally appeared in ‘Hypebeast Magazine Issue 32: The Fever Issue.’ Please visit HBX to grab your copy.

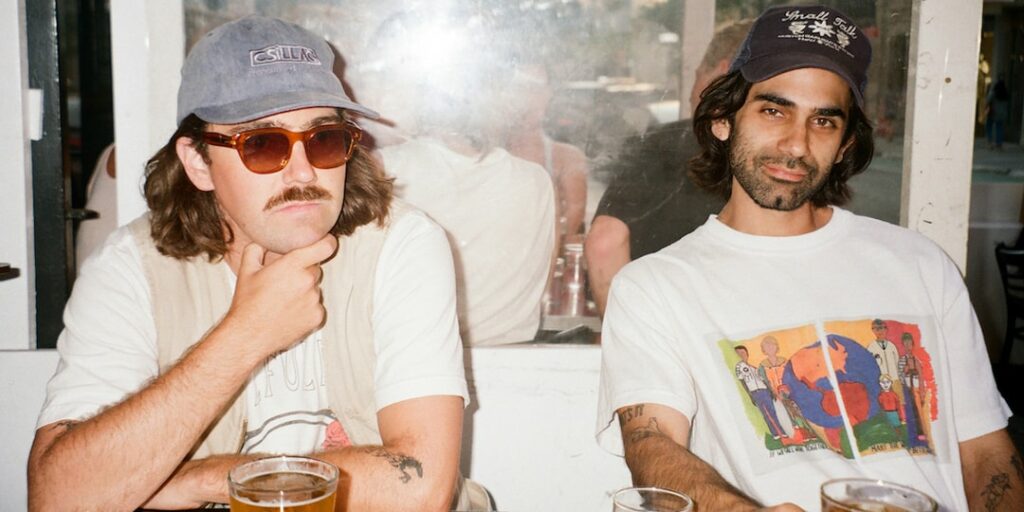

In another life, Nick Williams and Phil Ayers could have been renowned tattoo artists. The duo behind NYC-based clothing brand Small Talk Studio built its name making one-of-one garments embossed with hand-drawn illustrations and embroidered graphics. They’d drop a 24-hour custom order window on their Instagram, and the lucky few who nabbed a ticket would send the boys a list of visuals and personal reference points. Ayers and Williams would then mix and match the customer’s picks with a medley of “old faithful” images—essentially their version of tattoo flash sheets—that they’d painstakingly draw on denim pants, button-downs, and trucker jackets.

The illustrations form a constellation on a given garment, akin to someone who’s spent years getting inked until they have full sleeves and backpieces. And like tattoos, Small Talk drawings are bold statement pieces chock-full of imperfections that reveal the human hand, ensuring that each order is truly intimate and inimitable. Their visual vernacular ranges from timeless iconography like cupids, pin-up girls, botanical images, and baby devils, to niche cuts like vintage Tang logos, bootleg Bart Simpsons, and the 1996 Montreal Jazz Festival poster. The designs “almost turn into an I Spy composition,” says Ayers. The through-line amongst the disparate imagery is the customer’s personal interests (and Small Talk’s signature touch).

There’s an “element of trust between the customer and us,” the duo says. “They don’t know what we’re actually gonna draw on their garments, so it’s a big leap of faith,” one that results in a cherished piece that no one else in the world has.

Small Talk’s approach has led to a true-blue fanbase, including repeat customers, as well as a commission from Virgil Abloh before his tragic passing. Their reputation also catalyzed collaborations with brands like Adish, Karu Research, Carhartt WIP, and Gitman Vintage, where they were offered free reign to take the established labels’ garments and “freak ‘em” in their own style.

After a few years of focusing on customs, Williams and Ayers opened a studio on the 14th floor of a pre-war building, smack-dab in the heart of Manhattan’s Garment District. The space is cozy, well-lit, and adorned with Small Talk’s own illustrations on the walls and furniture. It’s also where they keep the designs for their first two cut and sew collections, one for Fall/ Winter 2023 and the other for Spring/Summer 2024.

Both collections include around two dozen unisex designs with few illustrations but lots of secondary treatment to the fabrics, such as dyes and embroideries. The fall release features a silk mohair jacket and wool pintuck trousers that Williams describes as a “psychedelic Western vibe,” whereas the spring collection was inspired by “arbor-glyphs,” or markings on trees, which manifests in garments like pants made out of crinkled gauze fabric that resembles the texture of bark. Small Talk still plans to continue its bespoke business, but the goal with the whole – sale items is to “find a visual language that bridges the gap between the all-over super graphic customs and [the designs] that are a lot quieter and more understated.”

The clothes will be offered in stores like Blue in Green, Colbo, and Cueva in New York, Super A Market, Hollywood Ranch Market, and Domicile in Japan, as well as boutiques in Los Angeles, Philadelphia, and Melbourne. Williams and Ayers want to establish “long-lasting relationships with more independent retailers, rather than immediately going for the big fish.”

Ultimately, the duo strives to make clothes that are “too personal to give away,” heirloom fits that are versatile and can be dressed up or down. And like a good tattoo artist, the source of each design should be immediately recognizable: a Small Talk Studio joint.1 of 3

Christian Michael Filardo2 of 3

Christian Michael Filardo3 of 3

Christian Michael Filardo

Prior to starting Small Talk Studio, did either of you have design or fashion experience?

Phil Ayers: Not traditionally. I worked at Pilgrim Surf + Supply for about three years and was doing free – lance illustration with a few different clothing brands. But before that, I worked in a totally different field and was just doing painting and illustration on the side. Both of us come at Small Talk from an art background, and that informs our approach to apparel design.

Nick Williams: We have a bit of an outsider perspective since we’re not traditionally educated in garment design. That flips the equation a little bit. When I moved to New York, I was working for a housing nonprofit and teaching art to adults at this supportive housing facility in Brownsville. For about eight months, I would go there three days a week and teach, and then work on Small Talk on my off days. Eventually, Small Talk got to the point where I could do it full-time.

What led to Small Talk being successful enough to focus on it exclusively?

Nick Williams: The transition from part-time to full-time happened really fast. It was basically a combination of good press—like an interview with Blackbird Spyplane and then a profile along – side a couple other designers in the Wall Street Journal—and also getting commissioned to make a custom piece for Virgil Abloh. This all happened in the summer of 2020 and it brought a lot more attention to the operation. I basically spent the summer trying to keep up with the orders that were coming in for custom garments. That fall, I felt that there was enough demand for the two of us to do this together full-time. We officially started as a duo in January 2021, and from seeing Phil’s work, I already trusted that we’d be able to collaborate together well.

How did things change once it became a partnership?

Nick Williams: It took about three months for us to really merge our styles. Phil’s style is a lot cleaner, with a little more saturated color, and he also has a heavier hand. I have a brushier style, and use lighter shading. We started experimenting on pieces together while talking about how to make the style a little more cohesive—not to the point where you couldn’t tell who did what, but just so that it felt like one piece coming from two sets of hands.

Phil Ayers: I brought in an old t-shirt that I practiced a couple drawings on. Then we just jumped right into passing custom pieces back and forth across the table to one another. I think it’s nice because even if there are apparent differences in the style of one drawing to the next, there’s so much going on in any given piece that when you just step back and look at the whole composition, it feels cohesive.

Does one of you excel more at illustrating certain kinds of imagery?

Nick Williams: We’ve been doing it together long enough now that we internally know who should do what. At this point, we both can do whatever comes our way. There are just certain things that one of us likes to do more than the other.

Phil Ayers: I think the big one that we joke about is that we get asked to do a lot of pet portraits. And I always tell Nick that’s on him. A lot of people want their dogs drawn on our jackets or pants.

Something I find interesting about Small Talk is that there’s a lot of diverse imagery used, but it all feels like it’s part of the same constellation. How would you describe the visuals that the brand gravitates towards?

Phil Ayers: It differs between the custom stuff and what we do for cut-and-sew. It should be noted that for every custom piece we do that’s a one-of-one, we have a dialogue with each customer and we ask them to send us a stream-of-consciousness list of references and images that are meaningful or significant to them. That’s the jumping off point for researching and sourcing all the images for a garment. At this point, we’ve built up a library of images, so maybe 60-75% of the illustrations are unique to that person, and then there are old faithful images that we like to draw and know will work well. It almost turns into an “I Spy” composition or something—a bunch of disparate objects that don’t necessarily have anything to do with each other, but you put ‘em all together on an individual customer’s piece and the thread that connects them is that person’s interests.

Nick Williams: We like to find some balance between imagery that comes from the natural world and commercial imagery. I think some of that has to do with our own lifestyles. Our studio is in Midtown near Times Square, so we’re constantly bombarded with all kinds of commercial and artificial graphics. It’s really fun to recontextualize those visuals. Plus, both of us just love the outdoors in general. Phil’s a big surfer. I love to climb. We both like to hike, camp, swim in lakes and rivers—all that shit. I feel like the juxtapositions come from our city mouse, country mouse lifestyle.

I also remember you telling me about a binder full of image references and ephemera you’ve collected, almost like a tattoo flash book?

Nick Williams: We have a few binders and a lot of that stuff has been scanned. Due to the pace of everything we’re making these days, a lot of our references come from digital sourcing, going back into the archive, and pulling stuff that fits. But then when we get a project like the one we just did with Karu Research and MR PORTER, where they gave us free reign to do whatever, we really dive into some weird shit. A lot of the imagery for that collaboration came from this old book called From India to the Planet Mars, which chronicles the life and work of this artist Hélène Smith. She held seances where she intended to communicate with a whole world of Martian beings and made automatic drawings in the process. I originally found the book on a public domain archive.

Phil Ayers: Similarly, when we did a capsule for Carhartt WIP last summer, we had a couple months to source imagery and we definitely got a lot of stuff from The Whole Earth Catalog. We also got a lot of references from our friend Kiyo, who has this massive, impressive collection of vintage outdoor gear called Monroe Garden. He has a permanent showroom in his apartment, and he showed us all these crazy old climbing and mountaineering catalogs from the ‘60s and ‘70s. We pulled a lot of images from those and incorporated them into those garments. 1 of 3

Christian Michael Filardo2 of 3

Christian Michael Filardo3 of 3

Christian Michael Filardo

What’s the process like when doing the illustrations for a custom piece? Do you have an idea of what the finished product will look like from the jump?

Nick Williams: We never really plan out the design of an entire garment at once. We usually start with one big image that feels like a good anchoring piece and then work out from there. Luckily, we’ve never had a situation where we’ve started that organic process and gotten to a point where it doesn’t work.

Phil Ayers: I think another cool part of the whole process is the element of trust between the customer and us. With most garments, especially expensive garments, you know exactly what you’re getting. Here, though, there’s an element of surprise. People are sending us references, but it’s a very vague, amorphous list of things. They don’t know what we’re actually gonna draw on their garments, so it’s a big leap of faith. There’s always a surprise, but fortunately, all our customers seem to be pretty happy with the final product.

It does remind me of tattoo culture in the sense that flawed or imperfect tattoos are actually better, in a way. An artist’s individual touch should show itself.

Phil Ayers: Yeah, it almost looks better and is more meaningful when you can see a small element of the human hand and human flaw in a particular drawing. You can tell it’s not mass-produced. I think people appreciate and respond to that.

Can you talk about the materials and design approach for the cut-and-sew collection?

Nick Williams: It helps to be able to put together a full collection where there’s 20-30 pieces that all play off of each other, kind of like putting together a body of paintings or sculptures where one thing doesn’t have to fully represent the brand by itself. We find something to nerd out on and get really deep into it. This past spring collection, it was a book of tree carvings—arbor glyphs. We’d collected a bunch of images, which made me think about leaving your mark on nature—mark-making and mark-taking. That was combined with really trippy depictions of the natural world, like medieval horticultural manuscripts and these hand-drawn QSL radio calling cards that truckers used to make and distribute. The latter doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with the natural world, but the calling cards had wild images that resonated with us, and the way the images were made and shared had a lot in common with the tree carvings.

Those are turned into a very loose aesthetic guide for sourcing fabrics, coming up with images to embroider, and creating treatments, which, in turn, inform everything from drawings on garments to embroidered motifs—and even the fabrics and material. For example, there’s a pant in the spring collection that has a bark-like texture to it, a crinkled gauze fabric. And for the 2023 fall collection, we went for a psychedelic Western vibe with pieces like a fuzzy silk mohair jacket. It all emerges from the same place that our custom garments would, but it’s just translated in a different way. Plus, people like to see the hand-drawn stuff side-by-side with the cut and sew items and how they inform and play off one another.

Phil Ayers: The cut-and-sew silhouettes are more like things that we want to wear, things that we feel have somewhat of a timeless appeal and a unisex quality about them. I also want to emphasize that on top of sourcing quality fabrics and dialing in our patterns and silhouettes, there’s so much secondary treatment to a lot of these garments. We have all these great vendors we work with here in the garment district, whether it’s an embroiderer, dye house, or specific printers. We start with a nice fabric, a nice fitting garment, and then add our own sort of visual language to freak it a bit. There’s a lot of experimentation and trial-and-error that comes along in those processes, but that’s the Small Talk way. It also ties it back to how we approach the custom garments. 1 of 3

Christian Michael Filardo2 of 3

Christian Michael Filardo3 of 3

Christian Michael Filardo

Have you noticed any patterns or trends among Small Talk consumers and fans?

Phil Ayers: We definitely have a solid recurring customer base, even with the custom garments. We’ve had a lot of people who’ve ordered two or three at this point, which is sick because we usually only leave the custom order window open for 24 hours. People are usually queued up waiting for that.

Nick Williams: It’s hard to say for sure, but obviously everything is at a pretty high price point. So there are definitely people who are heads and are willing to save up money or run the credit card up and purchase a piece, which is great because that’s also how I buy clothes [laughs]. New York is still our biggest customer base, but we’re both pretty hyped when we see orders come in from tiny towns in the Midwest. Imagining people in small towns rocking these really loud clothes makes me very happy. It’s very easy to wear whatever the fuck you want in New York because nobody bats an eye, but it’s a bit more of a risk to wear some of the stuff we design in a small town where you might stand out a bit more.

Is there an ethos or mantra you embrace that represents the Small Talk vibe?

Nick Williams: From a bird’s-eye view, the super-general ethos to how we approach everything is raw and DIY with very heavy attention to detail. That’s combined with high-end materials, durable construction, and meticulous execution. Somebody once described our work as heirloom garments in a very flattering way. They’re too personal to give away, but in the best-case scenario, they’re something that you would pass on to a kid or someone else special in your life when they’re no longer serving you.

Phil Ayers: We want our pieces to look good and be functional, but we also believe clothing should be fun, and our clothes are fun to wear. There’s so much minimalist stuff out there, and we obviously now have quieter pieces too, but we’re just trying to strike a balance with the louder stuff. Ultimately, we’re hyper-conscious of how much work and money goes into making each garment. So it’s important we make sure this shit is long-lasting and that these garments are special enough that people are going to make them cherished staples in their wardrobe for years to come.

Source: Read Full Article