We all love Bluey. So why was there an Australian kids’ TV crisis meeting?

By Karl Quinn

Ginger and the Vegesaurs (known in the UK simply as Vegesaurs) is one of the most viewed shows on the BBC’s iplayer.Credit: ABC

Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

In Coffs Harbour last week, 260 people gathered to share their love of, and interest in making, Australian children’s television. It was the first ever Australian Children’s Content Summit, and for organiser Suzanne Ryan it was an event that started in something like a state of despair and ended in one of heightened optimism.

“The whole reason behind the summit was to have something for our industry,” says Ryan, herself a producer for more than 20 years. “We needed it. It’s been a time when people’s businesses have closed, people’s shows have stopped, people have had to take jobs elsewhere.”

This is, she says, a “challenging time” for makers of children’s film and television content in Australia, because the removal in 2020 of obligations on the commercial free-to-air networks to commission and screen such content, and the failure (so far) to regulate the streamers, has led to “market failure”.

According to the most recent figures from the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA), in 2022 the Nine and Ten networks commissioned just one kids’ show each, while Seven commissioned precisely none. (Nine is the publisher of this masthead.)

Rock Island Mysteries was the only children’s show commissioned by Network 10 in 2022.Credit: Network 10

In total, that amounted to 95 hours of content. In 2019, the last full year under the old regulatory regime, there were 391 hours.

The trouble with making all that content, says Bridget Fair, chief executive of Free TV (the lobby group that represents the broadcasters), was that no one was watching it.

“By 2019, 90 per cent of C [suitable for children up to 15] and P [pre-school] shows had an audience below 10,000, and many programs were screening to fewer than 1000 children,” she says. “Unfortunately, that is not even close to an audience that commercial television broadcasters, who are required to provide free services funded by advertising revenue, can sustain.”

During COVID, with production schedules and ad revenues taking a massive hit, the Morrison government temporarily suspended the sub-quotas that set a minimum amount of children’s content for each of the networks. In October 2020, the requirement to make children’s content was scrapped entirely.

Had it not been for the injection of an extra $20 million over two years for the Australian Children’s Television Foundation (ACTF) for a pipeline of development (it has backed 39 projects) and production funding (20 projects), the sector might have been in an even worse state. And with that funding all but gone, the future is again on a knife’s edge.

“It’s abundantly clear that commercial broadcasters have all but abandoned investing in new programs for Australian children,” Screen Producers Australia chief Matthew Deaner said last week.

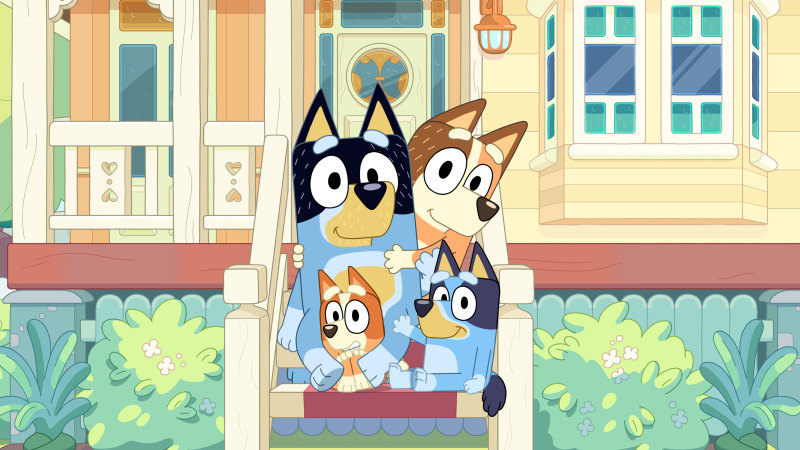

Bluey is the most successful Australian TV series ever made, across all genres and age groups.Credit: ABC

There are, SPA said in a release from the summit, “compelling social equity reasons for Australian families and children to have access to content that reflects shared experiences and life in Australia”. But the lack of interest in new Australian kids content from the commercial broadcasters and, for the most part, from the streamers leaves Aussie kids “with a strong diet of overseas programs … and Australian content … on high repeat”.

Now SPA is calling for an urgent review of the Australian Content and Children’s Television Standards (ACCTS) to ensure original local content has a place in the viewing diet of Australian children.

Yet at the same time as the sector teeters on the brink, it is being hailed for its phenomenal successes.

Ryan says the summit left her and others with the strong sense “that we do belong to an industry that makes great stories, that our content is shown all across the world, that we train and employ for long periods of time, and that was really exciting”.

But of course there is a but: Where would they be without the ABC?

“If it’s not the ABC then where?” asks ACTF chief Jenny Buckland of the challenge facing makers of children’s TV as they look for a home for their shows. “Only a few shows are getting up outside the ABC.”

“You go to international buyers, or you go to the ABC,” agrees Ryan.

Stan has recently commissioned its first children’s content, and Netflix has been active over a number of years with both co-productions with other broadcasters (MaveriX with the ABC, Dive Club with Ten, Eddie’s Lil’ Homies with NITV) and in its own right (Surviving Summer, Bureau of Magical Things). But there’s no question the ABC is the mainstay of children’s content in this country.

“We’ve got the biggest show in the world,” says Libbie Doherty, head of children’s content at the ABC. She is, of course, talking about Bluey.

The animated series from Brisbane’s Ludo Studio is, hands down, the most successful Australian TV show ever made, for any age group. And according to Doherty, its success is rubbing off on other shows.

Libbie Doherty, Head of children’s content at the ABC.

A source at the BBC recently told her Bluey was the number one title on the iPlayer streaming platform, with Vegesaurs (made by Sydney’s Cheeky Little production company) in second.

“Bluey has given us an opportunity to build out our preschool slate,” says Doherty. “Australian kids’ content is having a bit of a wonderful moment. People are actively contacting me from right around the globe wanting to work with us.”

‘[Children’s content] builds your subscriber base for the future.’

The problem is that having only one dominant buyer in the market isn’t good for anyone.

Fair insists that Free TV believes “children’s television programs produced in Australia … is important. But the answer is not to impose obligations to pump out programs that kids will never see, rather to incentivise production of programs that can be available on platforms that kids are watching.”

There’s no getting around the fact that for parents of small children in particular, a platform like ABC Kids or iview is far preferable to one with ads. And one where they can feel the content has been curated with the welfare of their kids in mind is preferable to the free-for-all autoplay regime of the wider internet.

The streamers could have a greater role to play, of course, but to date, and without anyone forcing their hand through regulation, most have steered well clear.

Kangaroo Beach is another Australian animated series proving a ht at home and abroad.Credit: ABC

For the ABC’s Doherty, it doesn’t make a lot of sense. More than 55 per cent of the content on iview is children’s (around one-third of it is Australian).

“I don’t understand why you wouldn’t see children’s content as an incredible part of your platform for that reason. It builds your subscriber base for the future,” she says.

The ABC spent more than $27 million on children’s content in 2021-22; the commercial broadcasters spent a little over $2 million. How much Netflix spent in the same period is unclear, but it has previously claimed that between 2019 and 2021 it invested “more than $58 million in new Australian kids content”.

Doherty insists she would be happy if the ABC didn’t have so much of the kids’ market to itself. “We welcome an ecosystem that has lots of great competition, and one where people see the value in children’s content,” she says. But unless there’s some sort of kids’ content requirements in the streaming regulations the government will soon reveal, that seems unlikely to happen.

“It shouldn’t be left to just the ABC to be doing Australian children’s content. All platforms should have the obligation to make it,” says Ryan.

People under 16 comprise 21 per cent of Australia’s population, she says. “That’s a significant part, they’re just not an audience.”

A Netflix/ABC co-production, MaveriX is set in the world of motocross racing.Credit: ABC

There’s a cultural imperative to make content that reflects their experiences back to them, and for the streamers, she’s sure there’s a business one too. “Families in this cost of living crisis have to make really serious decisions on how many streaming services they will keep, and if there’s not an offering for the children, these businesses risk losing subscribers.

“Why do we have to rattle the cage so hard to make the argument that this is an important part of Australia,” she adds. “It’s a no-brainer.”

Contact the author at [email protected], follow him on Facebook at karlquinnjournalist and on Twitter @karlkwin, and read more of his work here.

Find out the next TV, streaming series and movies to add to your must-sees. Get The Watchlist delivered every Thursday.

Most Viewed in Culture

Source: Read Full Article